| |

High Marks in Fatherhood

By Philip C. Chalk

Park Cities People, June 1985

He is no ordinary father.

Physicist, Professor, Investor, Architect, and Wicked Backhand Lobber—in all he attends to a certain instructive vocation. In the words of his wife, “he was born to teach.”

And teach he has: nuclear theory, campfire-building, quantum mechanics, jumpshots, medical physics, tire-changing, electromagnetics, and oatmeal making; the list goes on.

Jeff D. Chalk, III: B.S., B.S. again, M.S., Ph.D., and VIP to four immensely grateful offspring.

His is a secret shared by physicists and children alike: a love for all the questions. “Physics,” he once told us, “is the science of asking ‘why?’” And to a child, a physicist knows the answer.

“Shut the door,” one of us would snap, “you're letting in the cold.” No, he would correct, “you are letting out the heat.” And the potato that by chance balanced neatly on its end? “Equilibrium,” he announced. We filed it away.

His lessons enjoyed great range, from mountain climbs and meteor craters to kitchen chemistry and front-yard astrophysics (“The light you see from that star is 10 times older than the pyramids.”) What other father on the block could wisk away the tablecloth and explain the principle that left the ware in place?

(“Newton’s First,” as he folded the cloth up. “Objects at rest remain at rest.”)

His learning became our idiom. One rite of passage was to memorize the title to his doctoral thesis, The Two-Pion Exchange Contribution to the Three-Bodied Lambda Nucleon Interaction. Inevitably, one night came the question: “What does that mean?”

With unfailing willingness, he calmly turned once more to the blackboard hung by the breakfast table and studied it for a moment, chalk in hand. Then, drawing Saturn-like orbs with electron-path rings, he introduced to four eight-to-thirteen-year-olds the rudiments of particle physics; we took it in over chicken and beans.

He transcends science with ease. To his credit, all, some, or at least one of his children can do left-handed lay-ups, brave any slope on the mountain, beat him at bridge, jitterbug, and file a 1040A with supplements.

Always his example is before us: the hours taken off to coach years of YMCA basketball; the numberless weekends in ridiculous Bermuda shorts with an unruly throng of Boy Scouts; the patience of car trips on both coasts; and the gentle insistence that we turn this off, clean that out, finish these, stand up straight, and get home by twelve.

The Secret Weapon, however, is his most natural of traits: The reflective, ageless comment that makes far greater an impression than could any belt or bombast: “I simply see no conflict between true science and true religion;” “Well, you may very well not have time to have children, but they bring most of life’s happiest moments”; “I just cannot admire people who listen to loud music.”

The sage can have his handicaps, of course. Traffic can be blocked at twenty miles per hour less than the speed limit, while he travels in some unknown dimension. His children even mutter to him as he gazes wistfully through his dinnerplate: “Dad, your hair’s on fire.” From light-years away, the reply — “Mm-hmm.”

And he has had his setbacks. He was years late with the first son’s birds/bees discourse and never even bothered after that. Christmas electronics sets met with abject disinterest and were quietly replaced, a metaphor for true disappointment: None of his children shares his passion for science.

Indeed, there may have been some lessons learnt too well. Taught never to quit and always to follow their interests, his offspring have begun leaving home for Chicago, New York, and England, home only for a holiday or between migratory stages.

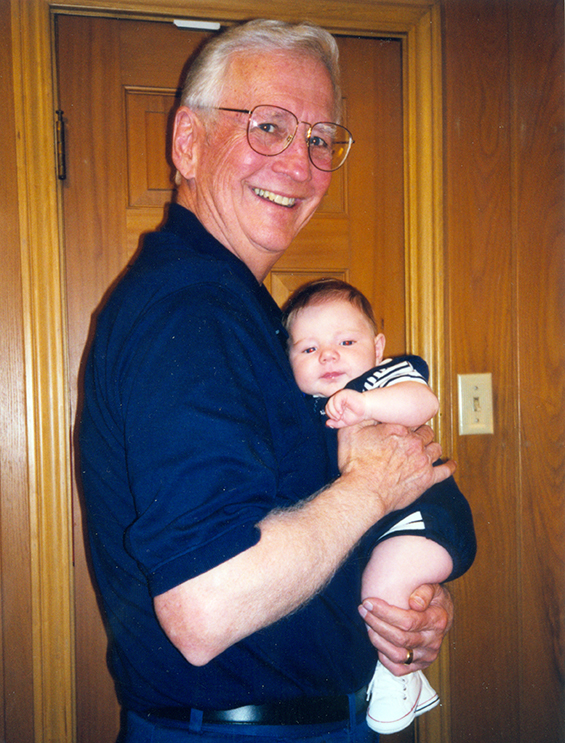

Recently, without warning, the old slate chalkboard slipped off the wall of its own accord and shattered on the floor. For a moment I thought it might have signaled an end to the lessons, especially with the children all grown and gone. Then, recently, at the christening of his new granddaughter Katherine, I saw the teacher again holding the baby girl softly in his arms. There was a new generation to be taught, and as the baby’s mother, aunt, and uncles will confirm, Katherine could not be in better hands.

Philip Chalk graduated from HPHS in 1980, and is now a student at Oxford.

|

|

|